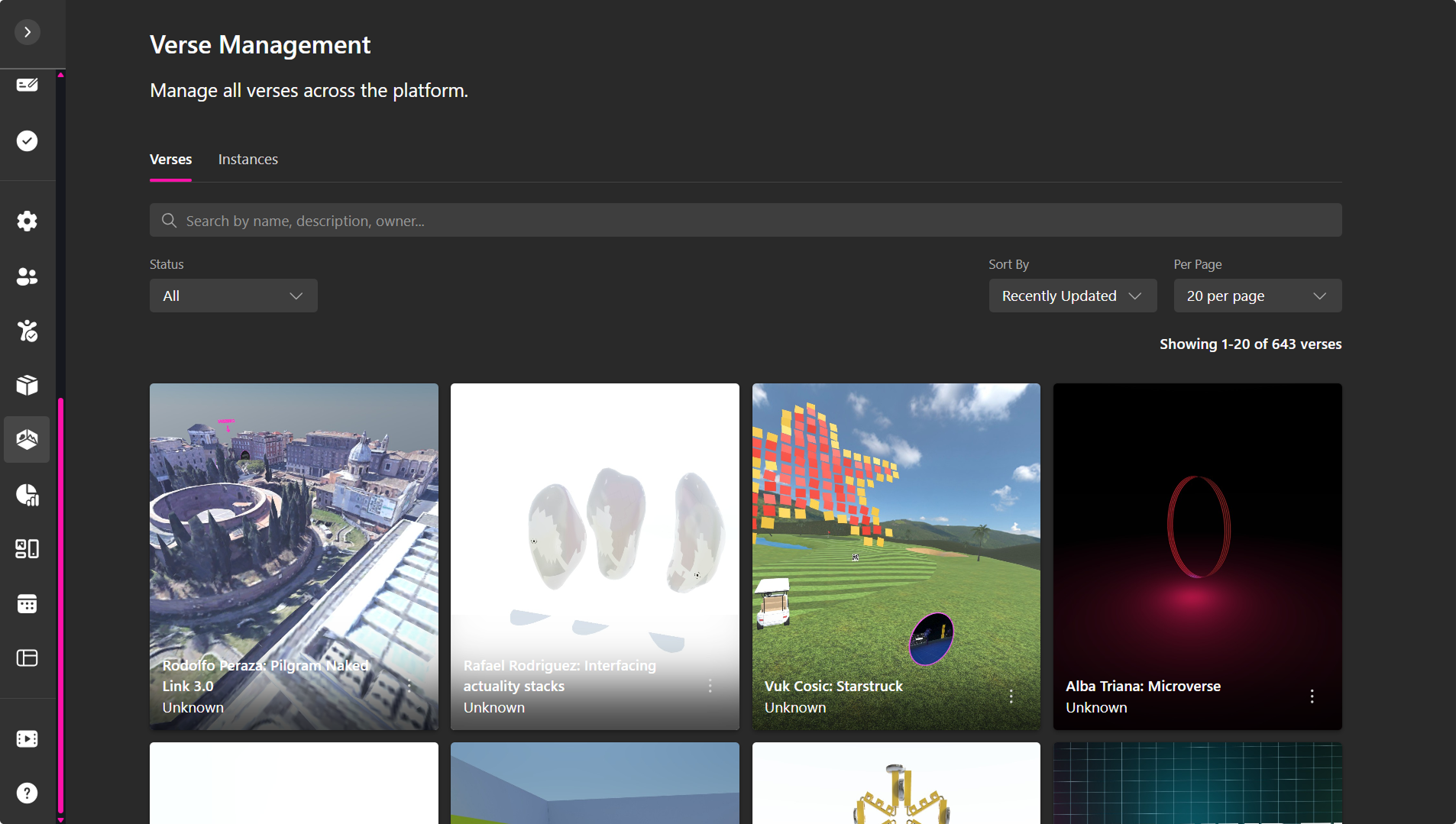

Vuk Ćosić | Filio Gálvez | Vladan Joler | Ernesto Oroza | Rodolfo Peraza

December 6, 2017 to March 2, 2018

Opening Reception: December 6, 2017 from 7 to 9PM

Co-curated by Rodolfo Peraza and Yuneikys Villalonga.

Media Under Dystopia 1.0 delves on the nature of our supposedly hyper-connected society and its promise of democracy at a moment when its core foundation is at risk and issues such as Internet Neutrality are under attack. How are individuals, as well as local contexts with their specific histories and politics, represented and served within the current digital landscape? How can the physical and the digital infrastructures of the Internet be mapped, and what do these new cartographies tell us about today?

As a laboratory of ideas, the exhibition showcases projects in different stages of completion –from the mere research; to the documentation of interventions; to long-term, process-based works. Many of these are the result of collaborations between people with very specialized, technical knowledges. This characteristic is not only reflective of the complexity of the subjects in question, but also of the nature of today’s multidimensional world that is often expanded to the virtual realm.

Vadlan Joler is interested in exploring what he calls the invisible infrastructure of the Internet. Together with a multidisciplinary team that includes experts on Internet forensics and data visualization from the Share Lab –a project he runs in Serbia– he has conducted research on the reach and impact of Facebook’s data collection backbone.

In the show, selected black and white prints from the many digital graphics conforming to his study shed light on the potential use and misuse of the 1.6 billion Facebook users’ data (likes, profession, friends, associations, etc.) that the company collects. By combining numbers and facts with methods of investigative journalism and critical media theory, the research reveals potential destinations of this information –in his own words, it “maps how our behavior is transformed into profit.”

Considered the most comprehensive of its kind so far, Joler’s project feeds the discussion on the need for algorithmic transparency – ie. the access and power of decision of users on the governing Internet rules and behaviors. As a professor of New Media at the University of Novi Sad in Serbia, Vladan brings the conversation to an academic setting where the discussion expands from cyber activism, economy and privacy to the social, political and environmental implications of this phenomenon.

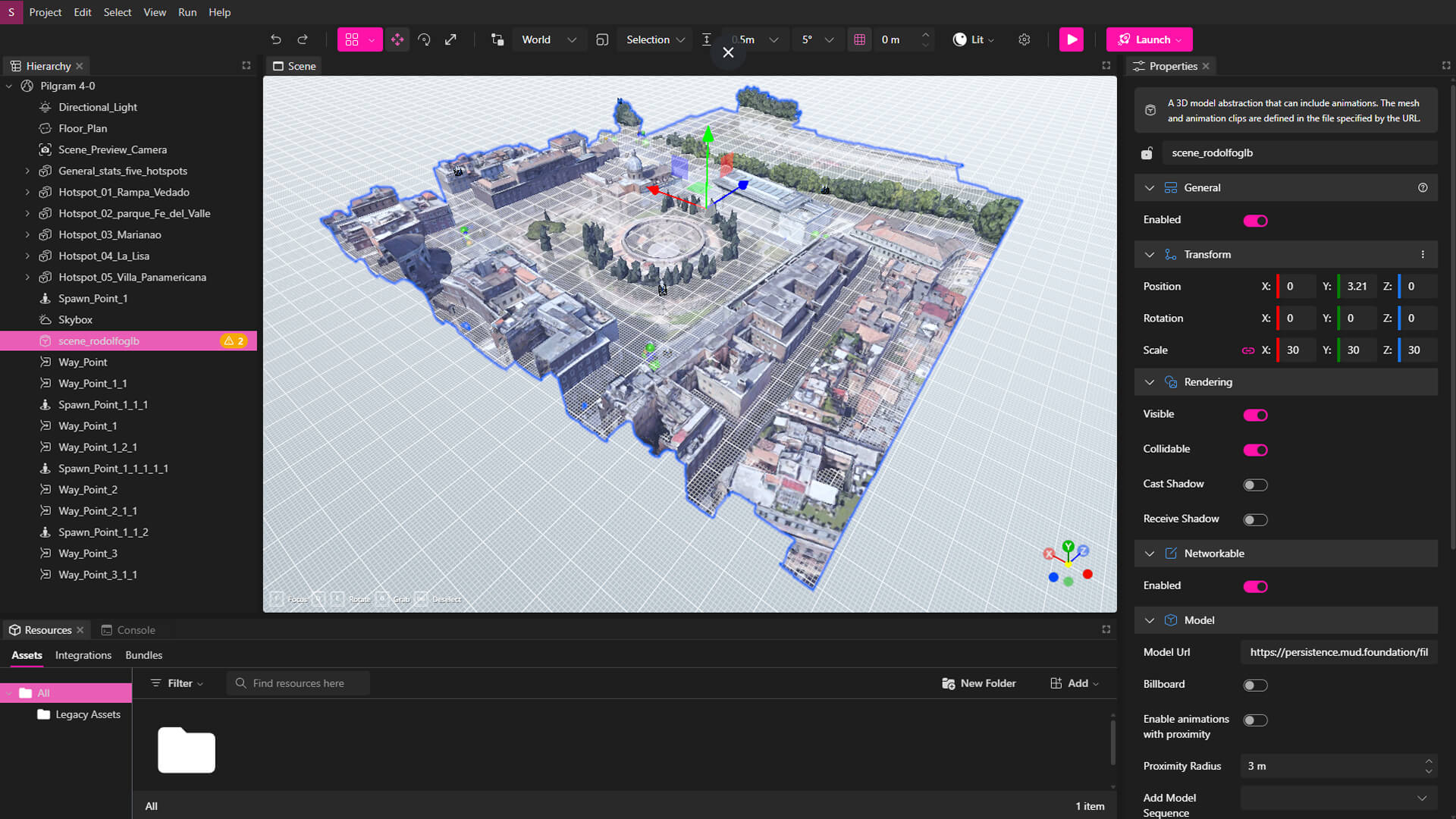

Exposing the nature of the abstract processes hidden behind the digital screen is also a key element in Rodolfo Peraza’s project Guerrilla Hotspot (2017.) In this case, though, collected data serves as source material for physical, immersive experiences.

Guerrilla Hotspot is an installation of free Wi-Fi hotspots that has been presented in Los Angeles, US., and San Juan, PR. before, and is now active at MUD Foundation to serve the Little Havana neighborhood where it is located. The artist provides these local communities (the immediate radius of people around the nanostations) with access to free Internet, in exchange for collecting the metadata they generate when using it –given their previous consent. The information collected is analyzed and then projected in the space, in real time. The tracking technology –similar to that used by commercial Internet servers– is hooked up to a VR software for data visualization. The information is converted into abstract maps of connections that, as it happens every day with the information we give to commercial servers, could be overseen and remain at a retinal level because of their beauty. Anyhow, the immediacy of the piece, which hopefully can be understood by a fragment of the Wi-Fi Internet users in the community, reveals the dynamics of connectivity and surveillance nowadays.

Cultivating this discussion, as well as Joler’s in Miami is of especial significance as this city is home to one of the biggest Internet Exchange Points worldwide. With offices in Europe, Latin America and the US, this company – Terremark Worldwide Inc. a subsidiary of Verizon Communications– silently controls a big percent of Internet traffic in the World.

Even when so close to Florida, the island of Cuba is, on the other hand, at the opposite end of hyper-connectivity. With a very controlled Internet access and, paradoxically, an increasing number of computer engineers and other technology experts, people in that country has managed to interconnect their home computers to create a popular underground network called SNET or “Street Network.” This intranet is a platform for gaming and for sharing information extracted from Internet, offline.

With the help of a local node administrator of SNET in Havana, Ernesto Oroza intervened this network with a piece titled “Si despierta un pájaro intercambian sus cabezas los jugadores” –which roughly translates into “if a bird wakes up, the players exchange their heads.” It is a quote from the poem Cielos del Sabbat (1960) by Cuban Writer and poet José Lezama Lima, written using the exquisite corpse method. The artist inserted a link to his project in SNET’s opening page. For a week, it directed users to another page where they could join an exquisite corpse poem game. Players were prompted to come up with one or two words that would add to the poem. This random and anonymous process was not only reflective of the nature of the network but also of the experience of collectiveness in Cuba. On the other hand, in a context where collective statements are only issued by official institutions, the piece symbolically became an alternative platform for freedom of expression.

An antecedent of Oroza’s idea is The World’s First Collaborative Sentence (1994), a piece by American artist Douglas Davis who, amazed by the incipient possibilities of the Internet of the time, thought to engage people from all around the world in what came to be a very long, international sentence. In this sense, “Si despierta un pájaro...” brings the Cubans’ intranet experience very close to that in America and other developed countries twenty years ago while, at the same time, it is a comment on the dynamics of those places that fall out of the speedy highways of the World Wide Web today. The resulting poem was physically brought to the States and printed fragments of it are given away in the gallery for people in Miami to take home in a process inverse to that of the “mulas” –mules– who, surpassing the regulations of the two countries, manage enter goods from Miami to the Island; another piece of alternative creativity of the Cubans.

From a similar anthropologic perspective and inspired by the Cuban resourcefulness, Vuk Ćosić conceived an Invisible Museum of Slavery (2015.) This work has not been realized yet and is presented through a series of documents. The idea for the project came out of an artist residency in Santiago de Cuba, Cuba. His host was a French coffee company who was refurbishing an 18th-century coffee plantation. As with many other buildings in Cuba, this historic site was being turned into a touristic destination and with it, its memory of slavery was being overwritten by the nostalgic exaltation of the ruins. “Very quickly, it because obvious to me that Cuba has not found the way to deal with its history of slavery and that current social relations are marked by deeply-rooted resentment,” declared the artist.

Given the lack of Internet, especially in isolated areas off the capital, and inspired by projects like SNET, the artist thought to set up a local router connected to a hard drive, as an intranet hotspot, containing “every available documentary, movie and book about slavery.” In this way, people who visited the area and connected to it would have a different take on its landscape and architecture. Furthermore, the very presence of a digital data archive on slavery twisted the new concept of that space into a memorial site that could be literally experienced.

The GIS (Google Image Search) Series by Filio Gálvez is the result of his experiments with the bandwidth of his Internet connection, which affects the speed and efficiency with which content reaches the screen. Gálvez slows down the strength of his Wi-Fi signal to search for images that relate to certain words or phrases of conflicting meaning (for instance, words extracted from the social media, in contraposition to others which were fashionable in the past). As images delay in loading, colorful squares with different patterns show up to take their place. Gálvez captures them through screenshots to later reproduce them individually, at a larger scale, in different mediums that go from paintings to prints. With this action, he is not only sublimating the glitches of the network, but also presenting to us another form of (aesthetic) perception of the digital content. In this sense, Gálvez’s works appear as reenactments of the experiments of net artist pioneers, from Kenneth Knowlton and Leon Harmon in the sixties to the Vuk Ćosić of the nineties, who looked at the computer code, especially ASCII, not as an intermediary between the machine and the user, but as an element intrinsic of the medium itself, with its own potential for communication.